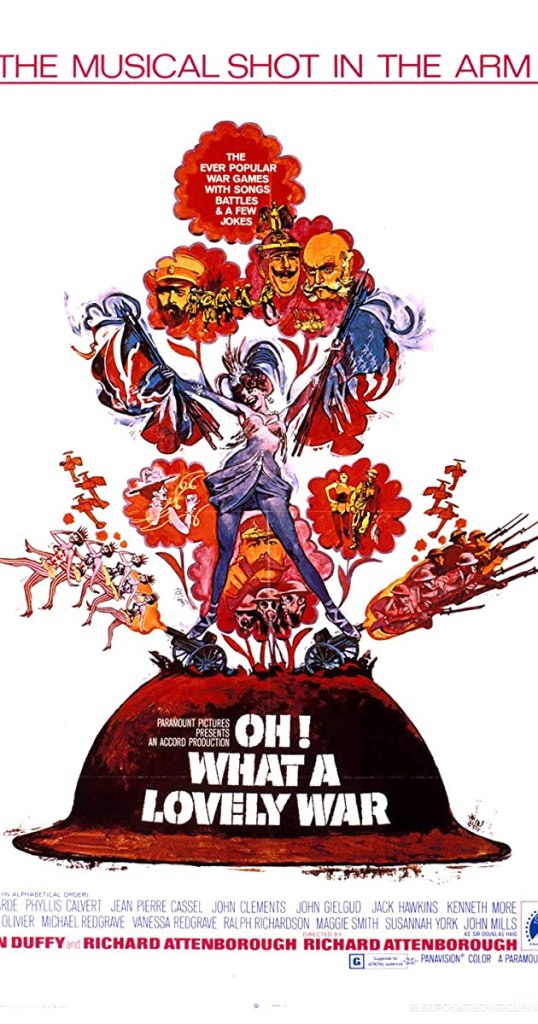

It is now more than a century since the end of the ‘Great War for Civilisation, 1914-1919’. That characterisation of the conflict features on the reverse of the British version of the Allied Victory Medal, and it now seems to be shot through with heavy irony. It is probably true to say that most British people consider the war as a monumental waste, a futile and pointless exercise. That view is what might be described as the ‘disenchanted’ view. However, we now see the Great War through the prism of the Second World War, the collapse of European empires and the end of Europe’s world dominance as the ‘Mighty Continent’. Further, the cultural interpretation of the Great War has, over the years, undergone a fundamental change. Since the 1960s in particular, the disenchanted view has held sway. In 1963 the left-wing ‘Theatre Workshop’ produced its highly successful stage version of the radio play, Oh! What a Lovely War. The play was subsequently turned into a major film, directed by Richard Attenborough. Oh! What a Lovely War satirised the conflict and helped frame a popular and enduring perception of the war as having no value at all. A similar approach characterised Bernard Bergonzi’s literary history of the war, Heroes’ Twilight, published in 1965. The view offered by play, film and academics like Bergonzi has continued to hold sway, though not unchallenged. Yet if we look at the writings of British ex-combatants in the inter-war period, we see a different, more nuanced picture.

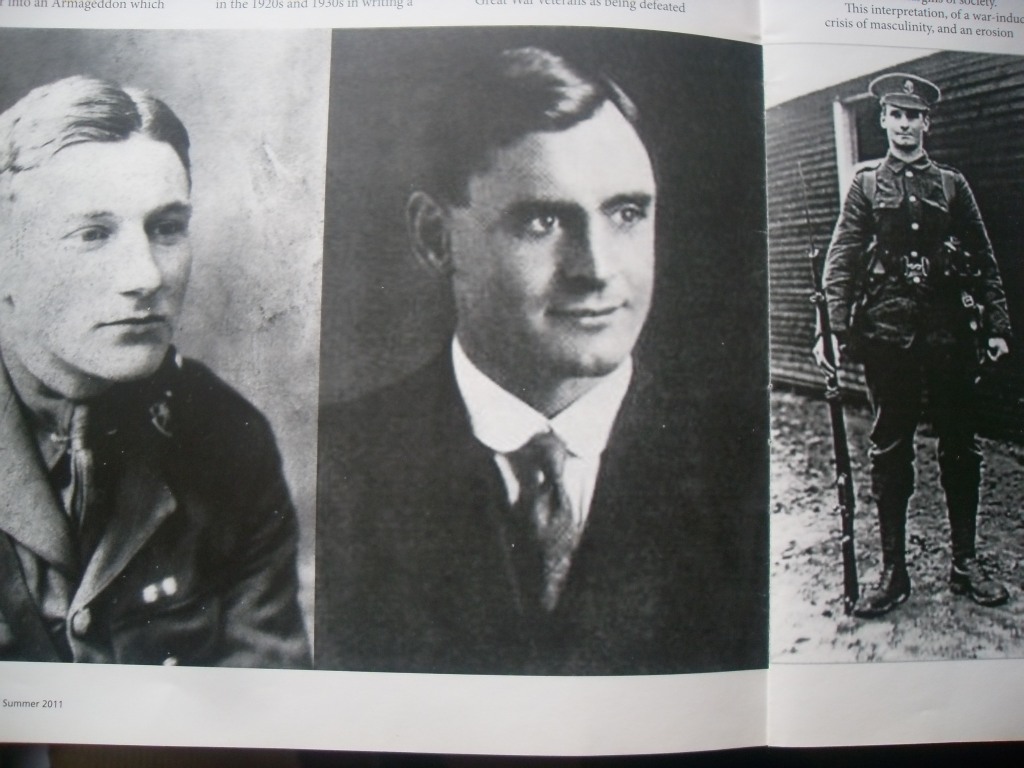

Although millions took part in the Great War, and saw combat, few wrote about it and only some 250-300 books by British ex-combatants were published between 1919 and 1939. There was a flurry of books by this group of men published immediately after the war’s end. For example, Wilfrid Ewart’s Way of Revelation: A Novel of Five Years (1921), and A.H. Gibbs’ The Grey Wave (1920). Publishers soon realized that the reading public’s taste for war memoirs and novels was limited as people attempted to return to some kind peacetime world. It was not until a decade after the Armistice that there was a new round of war writing by ex-combatants. The next few years into the early 1930s saw the peak of such publications both by British authors and by a small number of others published in translation. Books that are still well-known came out in this period, including Robert Graves’ Goodbye To All That (1929), Ernst Jünger’s Storm of Steel (first publication in English, 1929), Remarque’s All Quiet on the Western Front (1929), and Richard Aldington’s Death of a Hero (1929). Jünger’s book, first published in German in 1920, is a celebration of war and combatant manhood, and contrasts with Remarque’s worldwide best seller which can be seen as a total condemnation of the Great War. Yet both these books, along with those by Graves, Aldington and others, were condemned by a group of British literary ex-combatants as presenting a partial and inaccurate interpretation of the Great War.

One of these men was Douglas Jerrold, whose book, The Lie About the War (1930), attacked what he saw as the extremes of view encapsulated in the contrast of Jünger and Remarque. Jerrold, who saw action at Gallipoli and on the Western Front, stated, ‘not only was the war neither futile nor avoidable, but it was not believed to be either by the men who fought’. Instead, Jerrold posited what he termed was the ‘solid British point of view, which lies between the two extremes of despairing disillusionment and perfervid exaltation’. That ‘stolid British point of view’ was also one endorsed by another literary ex-combatant, Edmund Blunden. His own memoir of the war, Undertones of War was published in 1928, and is one of the enduring books on the war. Blunden was an academic, both at Oxford and in Japan, and a prolific writer, poet, and commentator. Along with his friend Siegfried Sassoon, with whom he shared passions for cricket and poetry, he was largely responsible for ensuring the legacy of Wilfred Owen’s poetry. Blunden probably spent more time in the trenches than any other British war poet (despite suffering from asthma), like Sassoon and Owen was awarded the Military Cross, was a patriot with deep roots in the English countryside, and a careful literary craftsman. He was also one of those literary ex-combatants who argued that the Great War was not without meaning. Instead, it was characterised by widespread and sustained heroism, and the vindication by servicemen of traditional codes of behaviour, especially endurance, courage and loyalty. This approach also characterised other writing by ex-combatants, including R.C. Sherriff’s Journey’s End (1929), Charles Douie’s The Weary Road (1929), Hugh Casson’s Steady Drummer (1935), and Guy Chapman’s Passionate Prodigality (1933).

We naturally read our own times and understanding into the history and literature of the past, and in terms of Great War literature and writing it is difficult not to interpret the stories of the men who fought from our own contemporary standpoint. That standpoint is heavily influenced by the knowledge of subsequent history, not least of the Second World War, but we are also influenced by the interpretations of the generations between us and the Generation of 1914. I hope I have suggested here that we need to make greater efforts to see the war as that generation did, especially in the interwar period. I have published a longer piece in this topic in The Historian (which can be found under ‘The Historian’ tab on the home page), and in Cultural and Social History, volume 8, no: 2, 2011 (which, sadly, lurks behind a very pricey academic paywall).