Academic journals & chapters (history) Academic journals & chapters (history)

Cullen, Stephen M.:

- Jews in the Communist Party of Great Britain : perceptions of ethnicity and class, A vanished ideology : essays on the Jewish communist movement in the English-speaking world in the twentieth century / edited by Matthew B. Hoffman, Henry F. Srebrnik, Albany: SUNY Press, 2016, pp.159-193.

- Review of Jews and the left: the rise and fall of a political alliance by Mendes, P. The Australian Journal of Jewish Studies, (2014) 28 . pp. 201-206.

- Fay Taylour : a dangerous woman in sport and politics, Women’s History Review, 21.2 (2012) 211-232

- ‘Jewish Communists’ or ‘Communist Jews’? : the Communist Party of Great Britain and British Jews in the 1930s, Socialist History, 41 (2012) 22-42

- “The Land of My Dreams” : The Gendered Utopian Dreams and Disenchantment of British Literary Ex-combatants of the Great War, Cultural and Social History – The Journal of the Social History Society, 8.2 (2011) 195-211

- The Fasces and the Saltire : The Failure of the British Union of Fascists in Scotland, 1932-1940, Scottish Historical Review, 87.2 (2008) 306-31

- Four women for Mosley : women in the British Union of Fascists, 1932-1940, Oral History, 24 (1996) 49-59

- Another nationalism : the British Union of Fascists in Glamorgan, 1932-1940, Welsh History Review, 17 (1994) 101-14

- Political violence : the case of the British Union of Fascists, Journal of Contemporary History, 28.2 (1993) 245-267

- The development of the ideals and policy of the British Union of Fascists, 1932-40, Journal of Contemporary History, 22 (1987) 115-36

- Leaders and Martyrs : Codreanu, Mosley and Jose Antonio, History, 71.233 (1986) 408-430.

History journals

Cullen, Stephen M.:

- Rotha Lintorn-Orman : the making of a fascist leader, The Historian, 135 (2017) 31-35

- Strange Journey : the life of Dorothy Eckersley, The Historian, 119 (2013) 18-23

- “Join Your Defence Volunteers”; the Manx Home Guard, 1940-1944, The Antiquarian : Newsletter of the Isle of Man Natural History and Antiquarian Society, 4 (2011) 49-61

- Other politics, other prejudices; the failure of the British Union of Fascists in Scotland, History Scotland, 11.2 (2011) 28-33

- Oxford’s Literary War : Oxford University’s servicemen and the Great War, The Historian,

110 (2011) 12-17

- Fascists behind barbed wire : political internment without trial in wartime Britain, The Historian, 100 (2008) 14-21

- The British Union of Fascists : the international dimension, The Historian, 80 (2003) 32-37

Books

Cullen, Stephen M.:

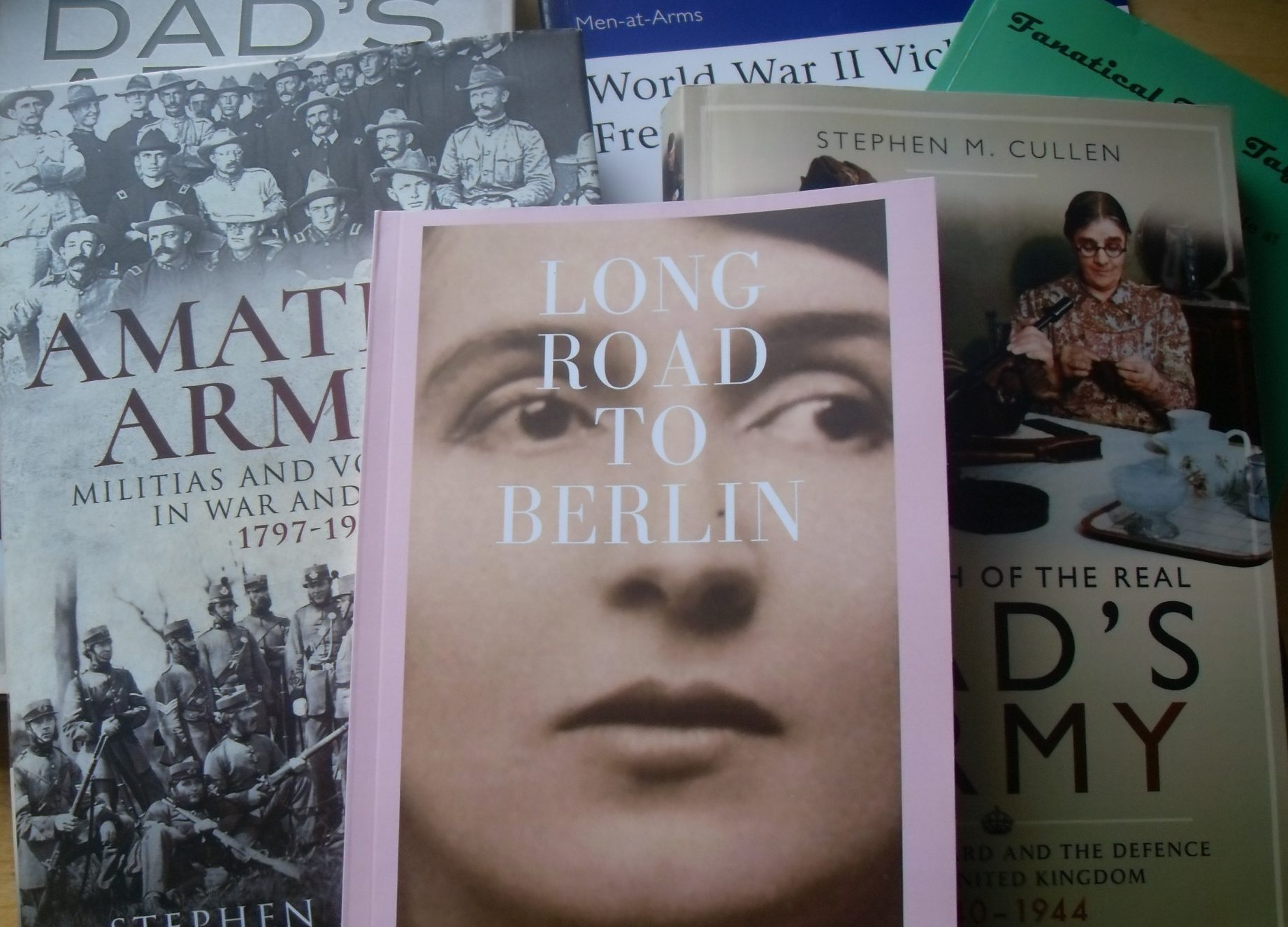

Long Road to Berlin: Socialism, Stalinism and Nazism; Dorothy Eckersley’s journey to German wartime radio, Warwick, Allotment Hut, 2021, ISBN: 9781838446505

Amateur Armies : Militias and Volunteers in War and Peace, 1797-1961, Barnsley, Pen & Sword Military, 2020, ISBN:978-1-52673-443-3

World War II Vichy French Security Troops, Oxford, Osprey, 2018, ISBN:9781472827753

Fanatical Fay Taylour : her sporting and political life at speed, 1904-1983, Warwick, Allotment Hut, 2015

In search of the real Dad’s Army : the Home Guard and the defence of the United Kingdom, 1940-1944, Barnsley, Pen & Sword Military, 2011, ISBN: 9781848842694

Home guard socialism : a vision of a people’s army, Warwick: Allotment Hut Booklets, 2006

The last capitalist : a dream of a new utopia, London, Freedom Press, 1996, ISBN: 0900384824 (as Steve Cullen)

Children in society : a libertarian critique, London, Freedom Press, 1991, ISBN: 090038462X. (as Stephen Cullen).

Academic journals (education)

Cullen, Stephen Michael (2019) Educational parenting programmes – examining the critique of a global, regional and national policy choice. Research Papers in Education, Volume 36, 2021 – Issue 4

Cullen, Stephen Michael, Cullen, Mairi Ann and Lindsay, Geoff (2017) The CANparent Trial – the delivery of universal parenting education in England. British Educational Research Journal, 43 (4). pp. 759-780

Cullen, Stephen Michael, Cullen, Mairi Ann and Lindsay, Geoff (2016) Universal parenting programme provision in England : barriers to parent engagement in the CANparent trial, 2012-2014. Children & Society, 30 (1). pp. 71-81

Cullen, Stephen Michael, Cullen, Mairi Ann and Lindsay, Geoff (2013) “I’m just there to ease the burden” : the parent support adviser role in English schools and the question of emotional labour. British Educational Research Journal, Volume 39 (Number 2). pp. 302-319

Cullen, Stephen Michael, Cullen, Mairi Ann, Lindsay, Geoff and Strand, Steve (2013) The parenting early intervention programme in England, 2006-11 ; a classed experience? British Educational Research Journal, Volume 39 (Number 6). pp. 1025-1043.

And more reports to government, NGOs, Third Sector, and conferences than you would ever want to wave a stick at. These can be found here: http://wrap.warwick.ac.uk/view/author_id/7651.html

Magazines:

Cullen, Stephen:

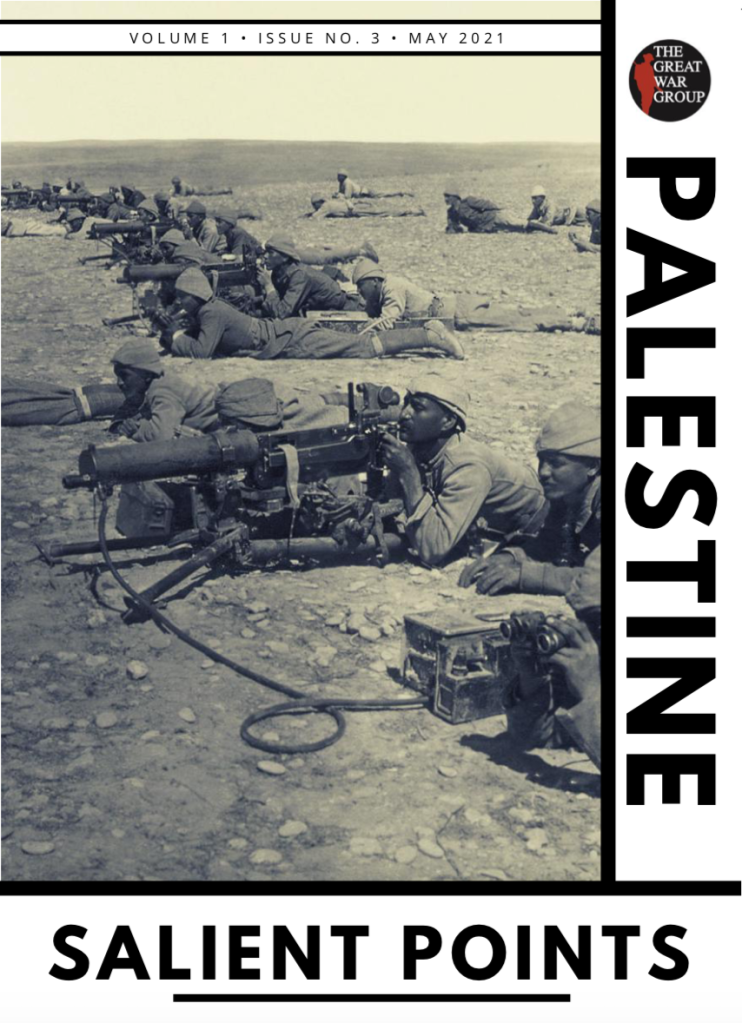

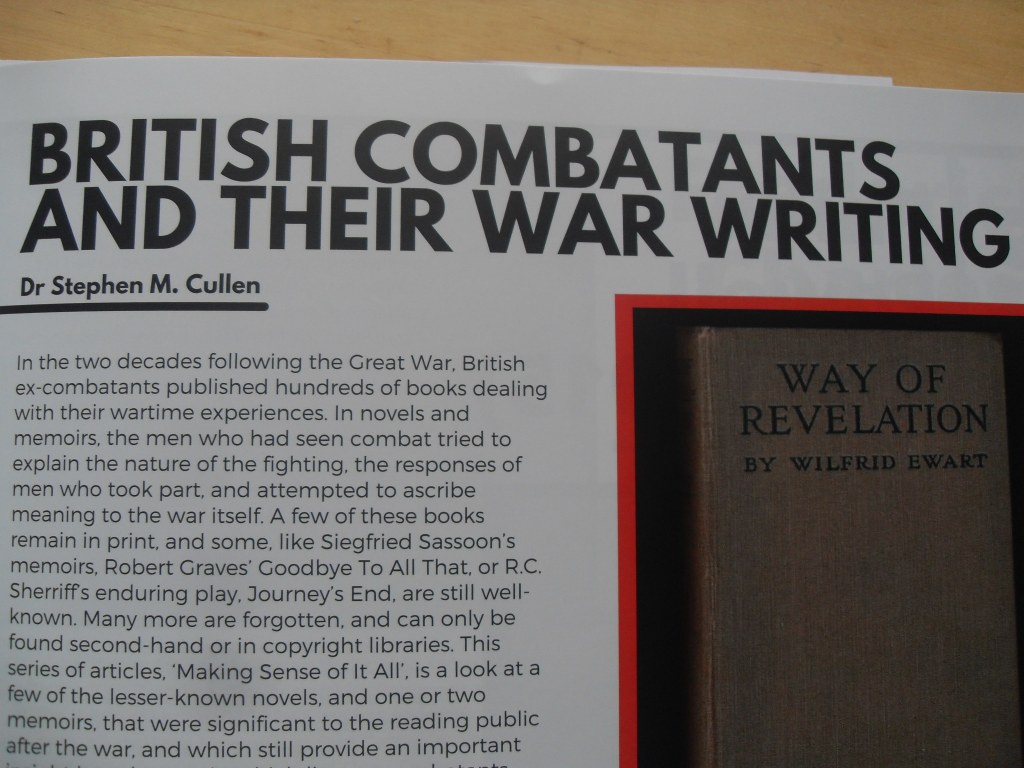

‘British combatants and their war writing’ column in Salient Points:

Volume 1 (3), May 2021: Wilfrid Ewart

Volume 1 (5), November 2021: Arthur Hamilton Gibbs

The Enemy Within, Military Illustrated, 274, March 2011, pp.8-15

Defending Mussolini, Military Illustrated, 263, April 2010, pp.8-16

Legion of the Damned, Military Illustrated, 238, March 2008, pp.24-31

The Great War Fiction of George Blake, Cencrastus Magazine, 67, pp.38-42

Rereading the Great War, The English Review, vol. 11, No: 2, November 2000, pp.38-41

‘A battalion of Christs’, Christian themes and motifs in Great War writing’, The English Review, vol. 17, no: 1, September 2006, pp.26-28

Behind Barbed Wire, Britain At War Magazine, Issue 46, February 2011, 39-44

Collaborationists in Arms: The uniforms and equipment of the Vichy Milice Française, The Armourer Militaria Magazine, July/August 2010, pp.24-28

Women in the Home Guard – official and unofficial, The Armourer Militaria Magazine, March/April 2012, pp.39-41

E-platforms:

Mum’s army : the forgotten role of women in the Home Guard, The Conversation, 5 Feb. 2016: https://theconversation.com/mums-army-the-forgotten-role-of-women-in-the-home-guard-54194

The troubled relationship between the state and parent, The Conversation, 4 Jan 2016: https://theconversation.com/the-troubled-relationship-between-the-state-and-parents-52996

How to help young people with autism stay on in education after school, The Conversation,

16 Jan 2015: https://theconversation.com/how-to-help-young-people-with-autism-stay-on-in-education-after-school-44683

Federal dreams aren’t just for Juncker – the far right has long had a pan-European flavour, The Conversation, 9 June 2014: https://theconversation.com/federal-dreams-arent-just-for-juncker-the-far-right-has-long-had-a-pan-european-flavour-27725

Bill Nighy fronts new Dad’s Army, but don’t forget the real Home Guard, The Conversation,

29 April 2014: https://theconversation.com/bill-nighy-fronts-new-dads-army-but-dont-forget-the-real-home-guard-26007

Poetry and short stories (mostly as Steve Cullen)

Can be found (if one knows which second hand bookshop to look in) in editions of the following little magazines:

The London Magazine (2003)

Northwords (2002, 1989, 1990)

Groundswell (2000)

Navis (1999, 1997, 1994/95)

Ibid (1995/96)

Romulus (1997, 1998)

Headlock (1998, 1995)

Odyssey (1995)

IBID (1995/96)

Magma (2000)

Scottish Book Collector (numerous)

And others I have forgotten about.

Anarchy:

Numerous articles from the 1990s & v early 2000s in Freedom, The Raven, & Total Liberty. (as Steve Cullen).